Enemies on the Couch. Why is War Endless?

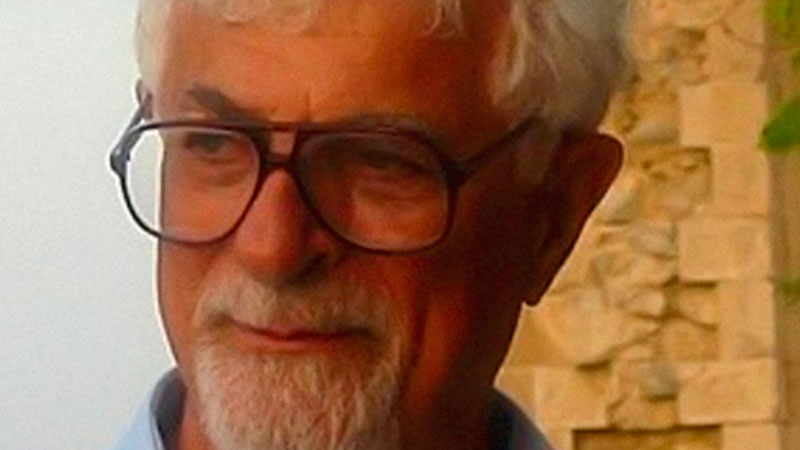

Interview with Vamik Volkan, M.D.

By: Donna Bentolila

Dr. Volkan, psychoanalyst, four time nominee for the Noble Peace Prize, spoke with me in October of 2013 regarding the development of large group identity that results in brutal confrontations amongst groups due to ethnic, religious or political differences.

History shows us that human beings have fought and killed each other since time immemorial. The advance in civilization has not been sufficient to arrest this aggression. The urgent problems faced by our world today lead us to think that this problem will continue to exist, perhaps in an even broader scale, due to the technological advances allowed by science.

Vamik Volkan is particularly schooled in these matters. In his professional career he has dedicated his life as observer, mediator and participant, to the study of ethnic conflicts, civil wars, terrorist attacks, identification with political leaders, and possible ways to intervene with adversarial groups who have long been in conflict with one another.

Dr. Vamik Volkan was born in Cyprus, is Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry of the Virginia School of Medicine, Emeritus training Analyst of the Washington Psychoanalytic Institute, Past President of the International Society of Political Psychology, Member of the Psychoanalytic Society of Virginia, The Turkish North-American Society of Neuropsychiatry and the American College of Psychoanalysts. Dr. Volkan is also the Senior Erik Erikson Scholar at the Erikson Institute of Education and Research of the Austen Riggs Center, Stockbridge, Mass. He has been awarded honorary Doctorates from the University of Kuopio, Finland, and from the University of Ankara in Turkey.

For almost three decades, Dr. Volkan coordinated interdisciplinary teams in multiple problematic areas around the globe. He was able to engage important representatives of “enemy groups” in order to sustain non-official dialogues for long periods of time. His work in this field has allowed him to develop new theories regarding the behaviors of large groups in times of peace and in times of war.

Dr. Volkan was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize four times, with the support of 27 countries. His wide and fruitful range of publications surpasses well over 40 volumes. His teaching has addressed clinical questions about mourning, psychotherapeutic technique, psychology of large groups – their ”traumas“ and “chosen glories”, the intergenerational transmission of trauma, the psychology of terrorist leaders and an autobiographical narration of his international work, including the founding of the Initiative for an International Dialogue.

“Enemies on the Couch: A Psychopolitical Journey Through War and Peace”, is his new book in which he illustrates how psychological factors affect international relations, and how an interdisciplinary group knowledgeable about those factors can advance and help to establish a peaceful coexistence.

My interest in his work is long standing. In 2005 I had the privilege of meeting him personally and beginning an exchange that has continued to the present. The generosity with which he shares his knowledge is admirable and his amazing international trajectory never takes away from the kindness and simplicity that characterize him.

Interview with Dr. Volkan

1) You are a Training and Supervising Analyst for the American Psychoanalytic Association who has worked in private practice. What led you to become interested in questions beyond the individual and to the dynamics of large groups?

In 1979 the then Egyptian president Anwar Sadat went to Israel. When he addressed the Israeli Knesset he spoke about the existence of a psychological wall between Arabs and Israelis and stated that psychological barriers constitute 70 per cent of all problems between these two people. This statement was a turning point in my professional life. The American Psychiatric Association’s Committee on International Affairs of which I was a member was given the task of examining Sadat’s statement. With the blessings of the Egyptian, Israeli and American governments, my colleagues and I brought influential Egyptians, Israelis, and then later Palestinians together for a series of unofficial negotiations that took place between 1979 and 1986. This is how my psychopolitical journey started.

2) Can you tell us how the Virginia Institute for the Study of International Affairs was founded? What are its aims and framework? How has it developed since its establishment in 1987?

When the Egyptian-Israeli unofficial dialogue series ended in 1987, I opened the Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction (CSMHI) at the University of Virginia’s School of Medicine. The CSMHI’s interdisciplinary team (made up of psychoanalysts, former diplomats, political scientists and historians) became involved in bringing together influential Americans and Soviets for a series of dialogues at the time when the Cold War was ending. Later we conducted years-long unofficial diplomatic dialogues between Russians and Estonians, Croats and Bosnian Muslims, Georgians and South Ossetians and Turks and Greeks. Apart from bringing opposing political representatives together for psychoanalytically informed psycho-political dialogues at different locations, we also evaluated the psycho-political environments in societies that had experienced massive traumas. For example, we studied Albania after the death of dictator Enver Hoxha and Kuwait after Saddam Hussein’s forces were removed from that country. I also participated in the former US President Jimmy Carter’s International Negotiation Network (INN) activities in the 1980s and 1990s. This helped me to meet many political leaders in various countries and investigate political leader-followers psychology.

I retired from the University of Virginia in 2002 and the Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction was closed three years later. During the last ten years I spent several months each year at the Erikson Institute of Education and Research of Austen Riggs Center in Massachusetts as the Senior Erik Erikson Scholar. In 2008 the Erikson Institute became the administrative home of the International Dialogue Initiative (IDI). Lord John Alderdice,Convenor of the Liberal Democrats in the House of Lords in London and a psychoanalyst, Robi Friedman, a group analyst from Israel and I are co-chairs of the IDI. With the help of two more psychoanalysts from the Austen Riggs Center, Edward Shapiro and Gerard Fromm, we have been bringing influential people from Iran, Israel, Lebanon, West bank, Turkey, Germany, Russia, United Kingdom and United States together twice a year and examining world affairs from different cultural and political views. Meanwhile, for over two years, I was involved in bringing together influential people in Turkey, both Turkish and Kurdish origin, in order to open a dialogue between them and come up with suggestions for the solution for the so-called “Kurdish problem” in Turkey.

I have been involved in international relations for over 30 years. These experiences directed me to begin to develop a large-group psychology in its own right.

3) In your new book “Enemies on the Couch, A Psychopolitical Journey through War and Peace”, you review some of the work that you have done during the last thirty years in war and conflict zones. How has your perspective and thinking evolved in regard to what you refer to as “large group identity”?

I use the term “large group” to refer to tens of thousands or millions of people, most of whom will never know or see each other, and who share a feeling of sameness, a large-group identity. A large-group identity is the end-result of myths and realities of common beginnings, historical continuities, geographical realities, and other shared linguistic, societal, religious, cultural and political factors. In our daily lives we articulate such identities in terms of commonality such as “we are Apaches; we are Lithuanian Jews, we are Kurdish; we are Slav; we are Sunni Muslims; we are communist.” Yet, a simple definition of this abstract concept is not sufficient to explain the power it has to influence political, economic, legal, military and historical initiatives or to induce seemingly irrational resistances to change such initiatives. When our large group is attacked, our large group narcissism is hurt, or we are humiliated as Arabs, as Jews, as Americans—we begin clinging to our large group identity. In certain situations, large group identity becomes much more important than our individual identity. Wars, war-like situations, terrorism, diplomatic efforts, shared losses and gains associated with shared mourning or elation are all carried out in the name of large-group identity. This is true even though this psychological source is usually hidden behind rational real-world considerations—political, economic, legal, and moral.

4) Can you describe what large group psychology is in its own right?

Considering large-group psychology in its own right means making “formulations” as to the unconscious and dynamic aspects of shared psychological experiences and motivations that exist within a large group and that initiate specific social, cultural, political, ideological processes that influence this large group’s internal and external affairs, just as we make formulations about the internal world of our individual patients in order to summarize our understanding of their internal worlds and interpersonal relationships. Let me give an example:

We are very familiar with a person’s externalizing his or her unacceptable self and object images or projecting unacceptable thoughts or affects on another person. This creates a personal bad prejudice. “I am not the one who stinks; my neighbor is the one who stinks!” If we want to understand at least one key aspect of societal prejudice, we will try to describe what happens when a large-group uses externalization and projection. When a large group finds itself asking questions such as “Who are we now?” or “How do we define our large-group identity now?”—usually following a revolution, a war, a humiliating economic trauma, or freedom after a long oppression by “others”—it purifies itself from unwanted elements. Such purifications stand for large-group externalizations and projections. After the Greek struggle for independence Greeks purified their language from all Turkish words. After Latvia gained its independence from the Soviet Union its people wanted to get rid of some 20 dead “Russian” bodies in their national cemetery. After Serbia became independent following the collapse of communism Serbs attempted to purify themselves of Muslim Bosnians and that led to tragedies such as the one in Srebrenica. There are non-dangerous as well as genocidal purifications. Understanding the meaning and psychological necessity of purifications can help to develop strategies to keep shared prejudices within “normal” limits and from becoming destructive.

5) What would you say is the most important factor as to why humans are often led to raise walls that end up separating communities in conflict with one another?

Even in the present globalized world where persons from different large groups live in locations with mixed populations, most of the time the “other” shared by thousands or millions of individuals is still on the opposite side of some kind of physical border: a legal political border of a nation, a geographical border created by nature between tribes or ethnic groups, or a border created by force when an enemy surrounds another large group. When there is no extensive conflict between neighboring large groups, a physical border remains simply a physical border; when there is a conflict, the physical border assumes great psychological meaning as the border separating large-group identities.

As a way of handling the opposing large groups’ anxiety, two basic principles begin to govern the interactions between enemies in acute conflict:

1. Two opposing large groups need to maintain their identities as distinct from each other (principle of non-sameness).

2. Two opposing large groups need to maintain an unambiguous “psychological” border between them.

If a political border exists between the enemies, it becomes highly psychological. The aim of creating a psychological border is due to our wish to keep what one large group externalized and projected onto the “other” from returning to the first large group.

6) What can you tell us about the manner in which the marks of trauma and historical conflicts are transmitted from generation to generation?

Massive societal catastrophes can occur for any number of reasons, including natural or man-made disasters, political oppression, economic collapse, or death of a leader, but tragedies, brutalities and deaths that result from the deliberate actions of other ethnic, national, religious or ideological large groups called “enemies,” must be differentiated from other types of massive shared trauma. This is because they involve severe large-group identity issues. When the “other” who possesses a different large-group identity than the victims humiliates and oppresses a large group, the victimized large-group’s identity is threatened.

When a large group traumatized at the hand of the “other” cannot reverse it’s feelings of helplessness and humiliation, cannot assert itself, cannot effectively go through the work of mourning and cannot complete other psychological journeys, it transfers these unfinished psychological tasks to future generations. All tasks that are handed down contain references to the same historical event, and as decades pass, the shared mental representation of this event links all the individuals in the large group and evolves as a most significant large-group marker (Chosen Trauma). The chosen trauma makes thousands and millions of people designated – "chosen" – to be linked together.

When individuals regress they “go back” and repeat their

childhood ways of dealing with conflicts contaminated with

unconscious fantasies and mental defenses. When a large-group regresses the large-group also goes back and inflames chosen traumas. For example, under Slobodan Milosevic Serbians inflamed the 600-year-old image of the Battle of Kosovo.

When enemy representatives get together for dialogues they become spokespersons for their large groups. When one side feels humiliated they reactivate the images of historical events. For example, while discussing current international affairs, Russians might begin to focus on the Tatar-Mongol invasion or Greeks may refer to the loss of Constantinople; both events occurred centuries ago. When such images of past historical events are reactivated within a large group, a time collapse occurs. Shared perceptions, feelings, and thoughts about a past historical image become intertwined with perceptions, feelings and thoughts about current events. This magnifies the present danger. Unless a way is found to deal with the time collapse routine diplomatic efforts will most likely fail. Today’s extreme Muslim religious fundamentalists have reactivated numerous chosen traumas and glories. We need to study and understand them in order to develop new and hopefully more effective strategies for a peaceful world.

7) If I understand your correctly, you view the ideas that Freud presents in “Mass Psychology and Analysis of the Ego” as lacking and insufficient in that they only address the intra-psychic. What can you say about your contribution to this question? How do your concepts of “large group identity,” “shared glory” and “shared trauma” complement Freud’s ideas in his work on Psychology of the Masses?

Freud was the great discoverer of the hidden aspects of an individual’s mind. He also described some aspects of crowds and large groups. Generally speaking he told us what a large group means for an individual. Large-group psychology in its own right as I defined above is something new.

8) In your book you underline how “the other,” being both enemy and friend, can quickly shift from one position to the other. You also remark how enemies are often alike, physically and psychologically. Can you please tell us more about this phenomenon and dynamic?

If someone shoots at you the danger is real. Enemies are both real and fantasized. Since one large-group externalizes and projects many unwanted things into the enemy the latter’s image includes elements that originally belonged to the first large group. In this sense the two opposing large groups become connected.

9) In your latest book “Enemies on the Couch” you underline the importance of the “Initiative of Interdisciplinary Dialogue” in order to offer models of thinking that can help us to better understand social conflicts. Please tell us more about this idea.

At the Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction (CSMHI) we developed the “Tree Model” to tame conflicts between opposing large groups. The application of this methodology takes years----like it takes years to analyze an individual. It has three basic phases:

1-Psychopolitical assessment of the situation (representing the roots of a tree).

2-Psychopolitical dialogues between influential members of opposing groups (representing the trunk of a tree)

3-Collaborative actions and institutions that grow out of the dialogue process (representing the branches of a tree).

In Enemies on the Couch as well as in my several other books I describe this methodology in depth and give illustrations of its application.

10) As a continuation of the last question, can you tell us how the knowledge that you have gained has helped you to create models to assist large communities after they have undergone massive traumas?

After a trauma at the hand of the “other” there are specific societal responses (due to specific circumstances and historical issues) mostly in the service of protecting and maintaining the large-group identity. There are also typical societal responses. For example, the large-group rallies behind the leader. If the leader cannot maintain “basic trust” severe splits and fragmentations occur within the large group; the large group focuses on minor differences between itself and enemy group; large group members experience increased large-group narcissism (it can be masochistic or malignant narcissism), magical thinking (or religious fundamentalism) and reality blurring; the physical border becomes the boundary of the large-group’s identity; the large group engages in behaviors symbolizing “purification;” the personality organization of the political leader becomes a significant factor in societal/political realities and so on.

After a massive trauma at the hands of enemies, or after a period of political oppression by a government the people in the victimized group experience a shared sense of shame, humiliation, and even dehumanization. They cannot be assertive, because expressing direct rage toward the oppressors would threaten their livelihoods and even their lives. Their helpless anger interferes with their mourning over losses that touch every aspect of their lives, ranging from their dignity to their property, relatives or friends. Shared unfinished psychological tasks are then passed on from generation to generation. So guilt experienced by people belonging to the victimizing group may also be involved in transgenerational transmissions.

How to deal with traumatized societies is a vast topic. The facilitating team needs to spend time in the field in order to assess destructive responses and find “entry points” to tame them. In many of my books, including in Enemies on the Couch, I give detailed examples.

11) How did you come to consider yourself professionally as a “political psychologist”? Does this self-designation interweave global and personal perspectives?

I am a psychoanalyst working off the couch in order to understand large group psychology and find ways to tame, when possible, some large-group conflicts. I never called myself a “political psychologist”. But, many persons refer to me using this term.

We should also remember that there is no single theoretical or practical point of view or application of political psychology. Since I am also a psychoanalyst, I tried to examine both, conscious and unconscious motivations of how people with different large-group identities behave in peaceful or in stressful times. Other types of political psychologies depend more on the “logical” evaluations of conflicts and on “logical” solutions.

12) History shows us that humans have been slaughtering each other from time immemorial and that man will continue killing and murdering each other, perhaps in even larger numbers given the technological advances man has achieved. How do you understand the place of aggression in human beings? You seem to think, not without a dose of pessimism, that men will continue to slaughter each other.

There are various psychoanalytic theories on “aggression.” From a practical point of view, the human aggression as expressed in large-groups is here to stay. Psychoanalysts need to evolve a large-group psychology in its own right further if we wish to be effective in having a role in societal and international arenas.

Dr. Volkan, thank you for sharing your thoughts and ideas on this all important subject for both us as psychoanalysts and for all of humanity.

Nota Bene: A Spanish language translation of this interview first appeared in volume 25 of the cultural online Journal Letra Urbana.

Donna E. Bentolila, L.C.S.W. is a Past President (2014) and a board member of the Southeast Florida Association for Psychoanalytic Psychology (SEFAPP). She is a Teaching Analyst at the Florida Psychoanalytic Institute and a member of the American and International Psychoanalytic Associations. She maintains a private in Boca Raton and in Miami.

![]()